Unlock the real potential of real estate

VTS brings every person, process, and AI agent together, so the industry can move faster, smarter, and more profitably.

Explore the PlatformHome to over 13b sf of assets across the globe

In an industry where collaboration drives revenue, silos are expensive

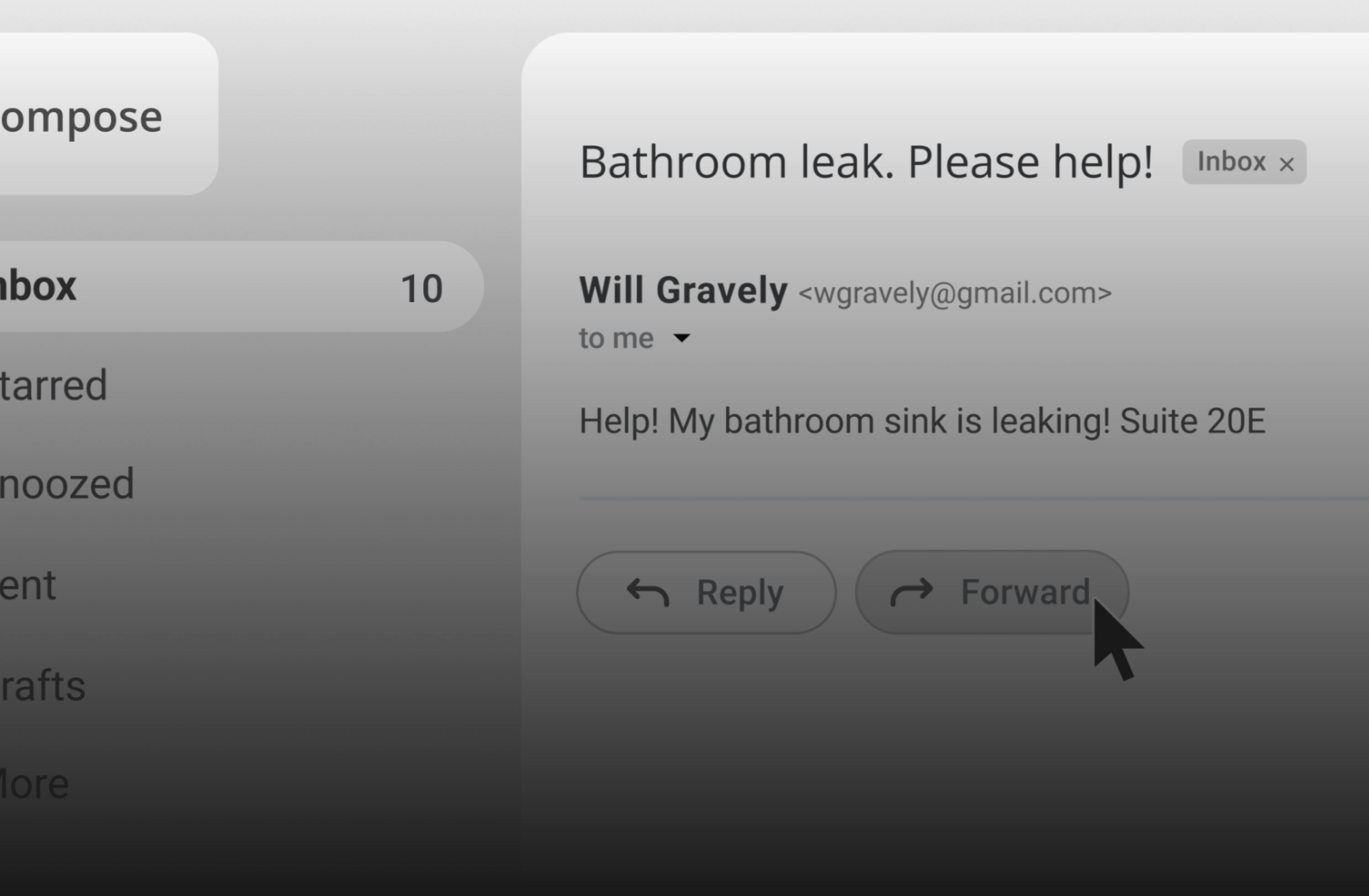

Asset management, leasing, property management, and marketing all play a role in delivering the revenue picture for a building. VTS brings these teams together in a single platform to work together with unparalleled speed and intelligence.

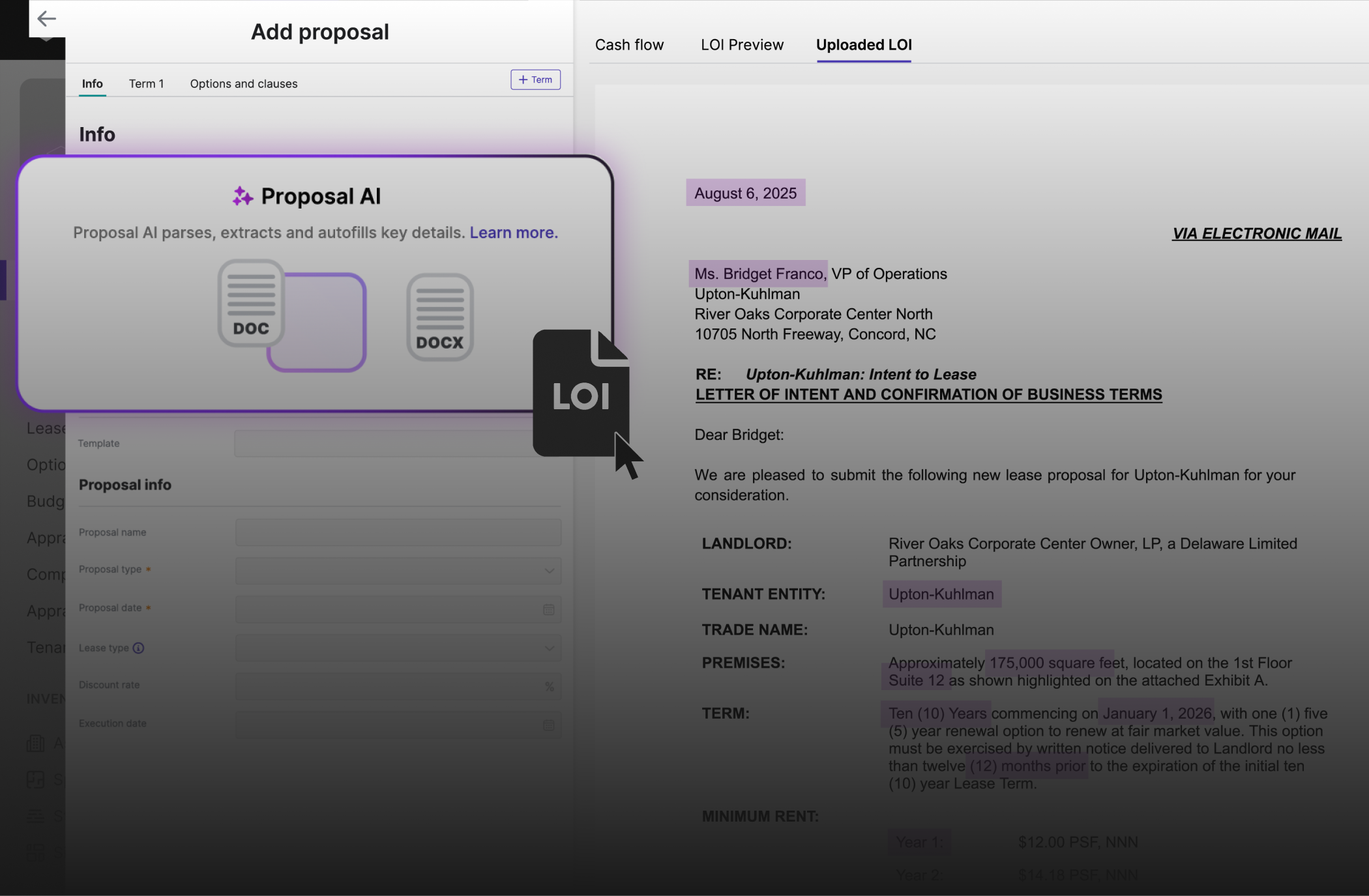

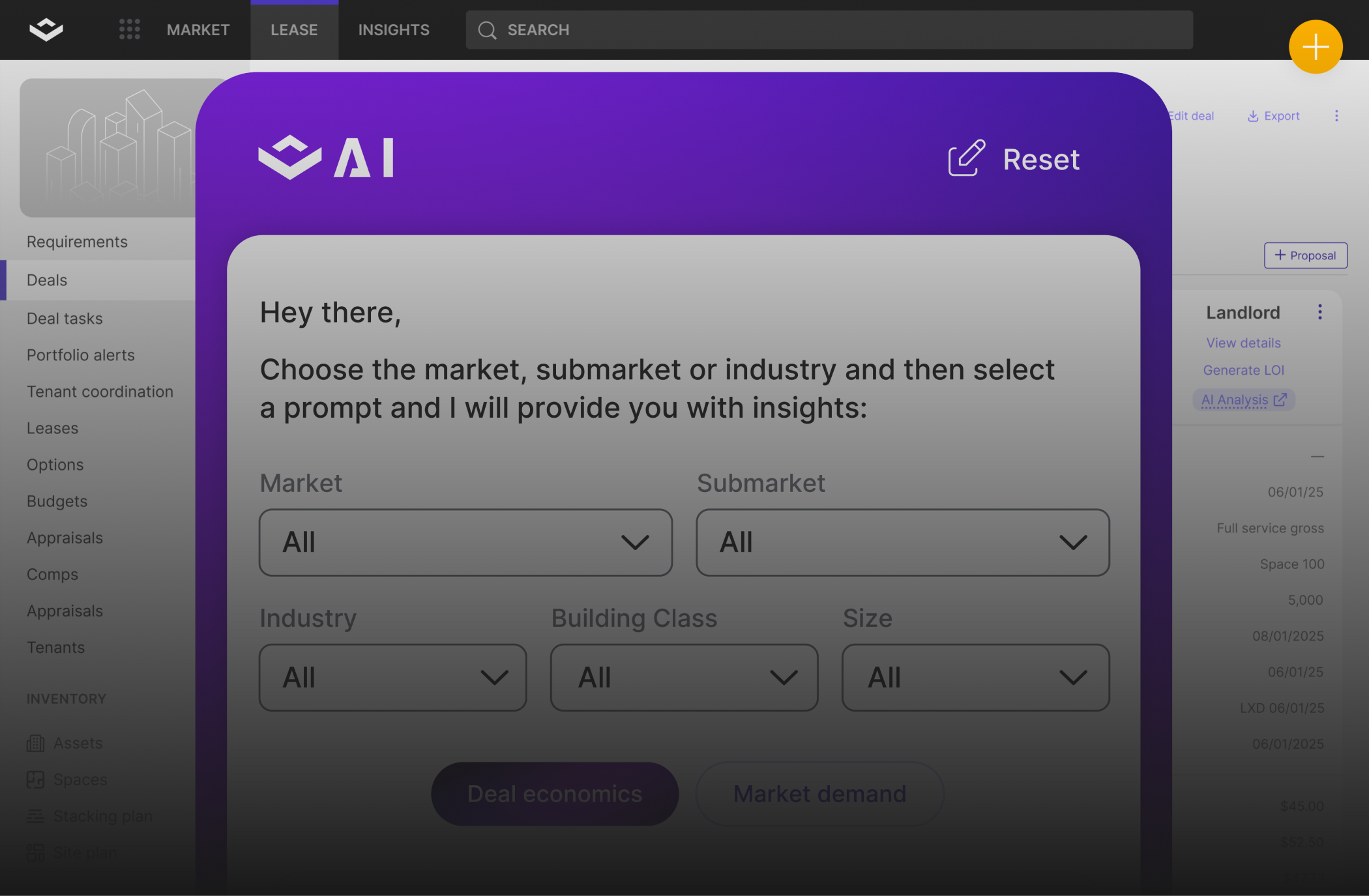

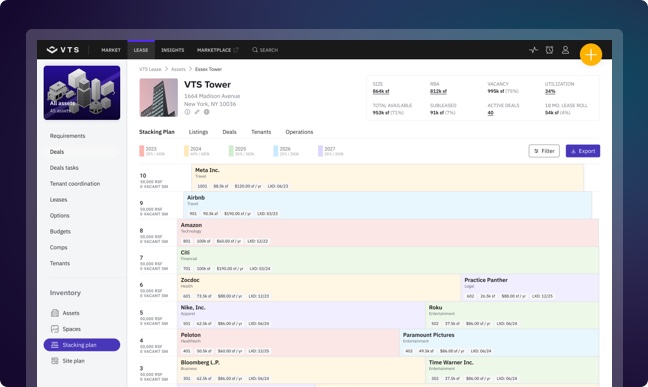

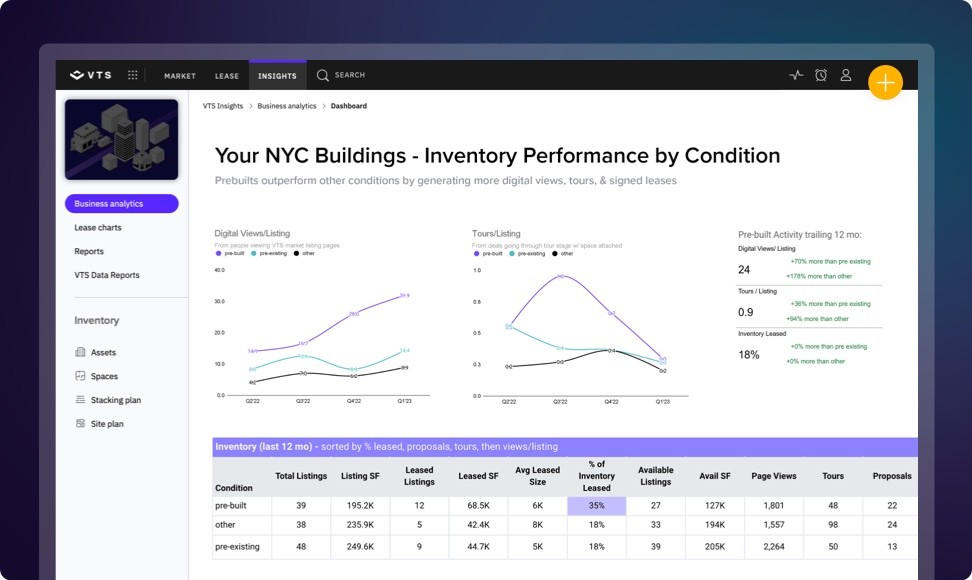

VTS Lease powers your entire leasing strategy, from inquiry to renewal, in one central app that delivers a clear picture of portfolio health.

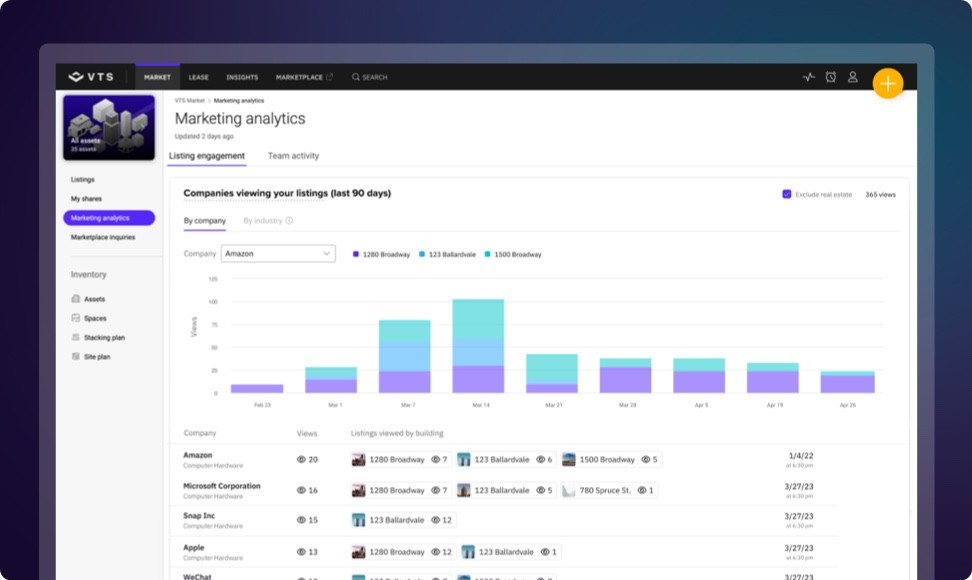

Deliver virtual content for your spaces across every digital marketing channel and measure its impact on leasing activity.

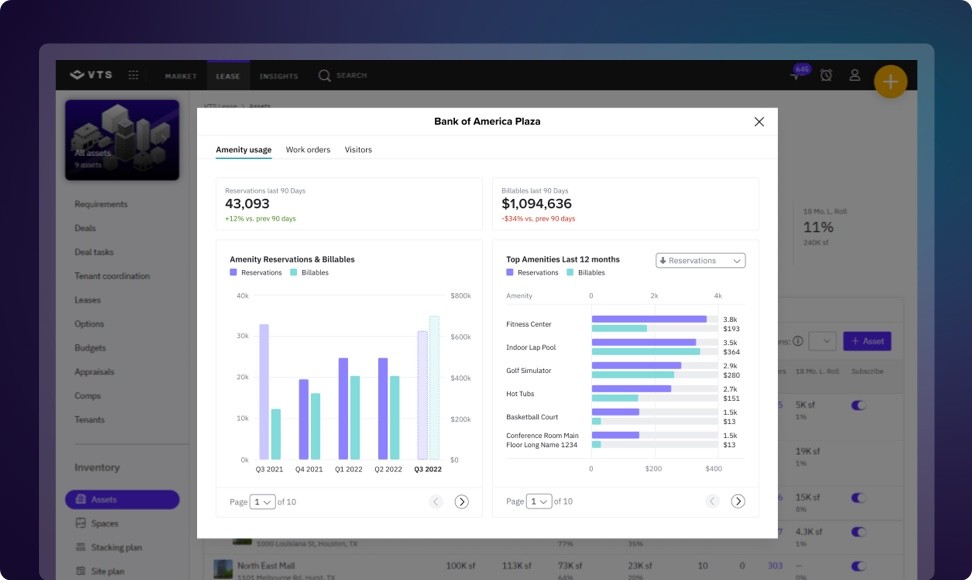

Give tenants a seamless, personal experience in your building and across your portfolio – all in one app.

Reinvent your investment strategy with the industry’s first predictive market research solution.

VTS is more than just technology, software, and insights

It's a dedicated team of experts inside VTS who know the ins and outs of CRE.

Learn more

Mission-critical technology for CRE organizations across the globe

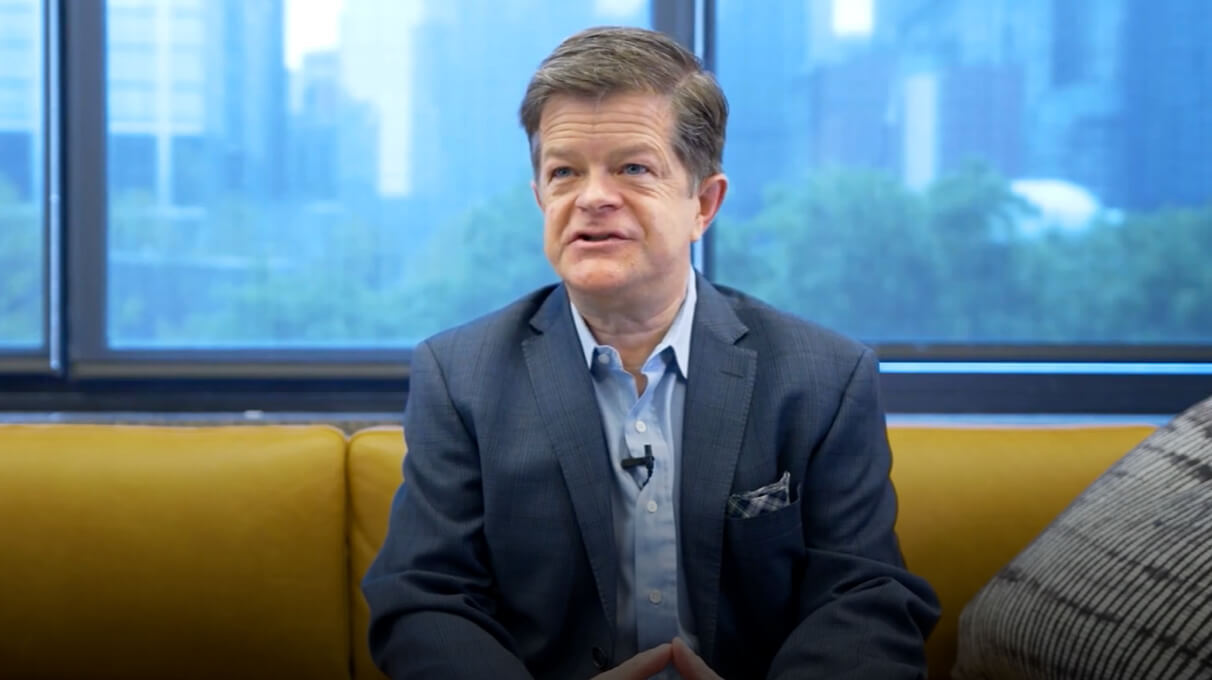

Hear from the industry's most influential landlord and brokerage organizations about the impact VTS has on their teams.

VTS Resources

Centralize your technology and insights

VTS Activate integrates with top CRE technologies so you can centralize your property operations.

Platform Innovations

See what's new and improved for customers across the VTS Platform.

VTS Blog

Dive into our library of industry insights, Q&As, and more.